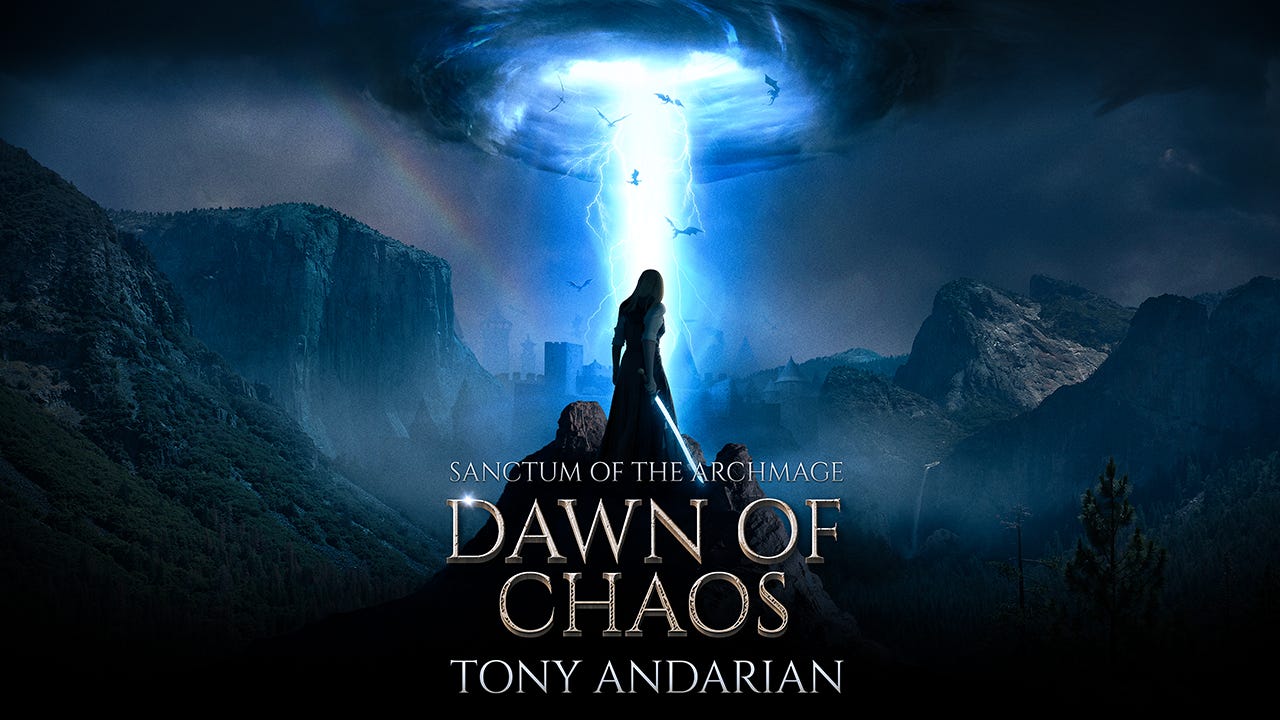

Randia's Character Arc in Dawn of Chaos

I had a very interesting dialogue with Grok this morning about my book, Dawn of Chaos. It offered to provide an analysis of the character arc of the protagonist, Randia Killraven.

I had a very interesting dialogue with Grok this morning about my book, Dawn of Chaos. After I pointed it to some sources and critiques to “grok,” it offered to provide an analysis of the character arc of the protagonist, Randia Killraven. It was so good that I decided to repeat it here. It does contain spoilers, so reader beware.

Princess Randia Killraven serves as a central protagonist in Dawn of Chaos, the inaugural volume of Tony Andarian’s Sanctum of the Archmage saga. Her character arc embodies a deliberate narrative choice, emphasizing transformation driven by external cataclysm rather than introspective self-discovery. This analysis draws upon textual excerpts from the novel and the author’s explanatory remarks to delineate her progression, highlighting key phases: initial independence, crisis-induced realization, emotional confrontation, and emergent resolve as a leader. Randia’s development aligns with the saga’s thematic core—the tension between personal autonomy and authoritarian imposition—positioning her as an exemplar of resilient heroism amid existential threats.

Initial Characterization: Independence as a Free Spirit

At the outset, Randia is portrayed as an artistic and independent individual, unburdened by profound internal conflicts. She is not depicted as spoiled, as some interpretations suggest, but as a self-assured heir who prioritizes personal choice and creative pursuits over rigid royal duties. This foundation is intentional, as Andarian explains: the main characters, including Randia, “already know who they are and are happy with it.” Her reluctance to embrace the throne stems from a preference for autonomy, reflecting the novel’s broader conflict between individual liberty (exemplified by Randia and Archmage Lenard) and elite obedience (embodied by the antagonist Zomoran). This phase establishes Randia as a bardic free spirit, content in her identity, which sets the stage for external forces to compel her evolution.

Crisis and Realization: Confronting External Threats

The demonic invasion orchestrated by Zomoran propels Randia’s arc into motion, transforming her from a reactive participant to a proactive agent. In the excerpt from “The End of the Beginning,” Randia arrives at a cliff overlooking the ravaged Silver Star Adventurer’s Academy, witnessing widespread destruction: fires, invading demons, and the collapse of her grandfather’s tower. Her actions—sprinting to the edge and stumbling forward—convey urgency and horror, while her internal thoughts reveal deepening despair: “I’ve failed them, I’ve failed them all. I’m too late, and now the world will pay the price.” This moment underscores her sense of personal responsibility, not as an inherent flaw, but as a burden imposed by the catastrophe. The scene illustrates how external devastation amplifies her emotional stakes, forcing her to grapple with failure on a global scale without prior internal voids to fill.

Andarian reinforces this external driver as purposeful, noting that Dawn of Chaos is “the story of how an external force of brutal evil compels people who already know who they are to change and grow, in ways they never expected or wanted.” Randia’s arc thus avoids conventional tropes of self-doubt resolution, instead focusing on adaptation necessitated by unrelenting adversity.

Emotional Confrontation and Internal Conflict

A pivotal escalation occurs in “The Crucible” (Chapter 17 of Hell Gate), where Randia’s internal reflections reveal the depth of her transformation. Resting a blade against her forehead, she allows rage—a sensation “alien to her kindly soul”—to surge through her, granting “comfort, confidence, determination, and clarity.” This emotional shift marks a critical juncture: she acknowledges her prior promises (e.g., to her brother Gerard) as “empty words,” recognizing herself as a “frightened victim” who has merely reacted by fleeing and mourning fallen protectors. The excerpt delves into her core fear: “It wasn’t the demons that truly frightened her. It was the woman she would have to become to fight them.” This introspection highlights an internal conflict—not rooted in pre-existing insecurities, but in the dread of necessary metamorphosis. By resolving to “let go of that fear,” Randia transitions from passivity to agency, embracing a warrior ethos to provide the “guidance, leadership, and inspiration” her people require.

This passage exemplifies Andarian’s design for resilient characters who channel grief into vengeance, refusing to let mourning hinder resolve. Randia’s arc, as the author states, is “at the heart of the first volume,” symbolizing the saga’s emphasis on unyielding opposition to evil “no matter how ruthless and powerful it may be.”

Emergent Resolve: From Free Spirit to Warrior Princess

By the novel’s conclusion, Randia emerges as a warrior princess, her independence forged into purposeful leadership. Her growth is not a quest for meaning but an enforced evolution, aligning with Andarian’s intent to appeal to readers who value arcs of compelled adaptation over internal quests. While external catalysts dominate, subtle emotional layers—despair in failure, alien rage, and fear of self-transformation—add nuance, countering critiques of underdeveloped mourning or realization. The arc culminates in a vow of justice, positioning Randia as a beacon of defiance, with foreshadowing of her continued role in subsequent volumes.

In summary, Randia’s character arc in Dawn of Chaos is a structured progression from autonomous contentment to resilient command, driven by apocalyptic external pressures. This design, as articulated by the author, prioritizes thematic coherence over conventional introspection, resulting in a protagonist whose development enriches the saga’s exploration of liberty and resistance. Such an approach may not resonate universally but effectively serves the narrative’s philosophical underpinnings.

As I said, I thought this was a pretty accurate analysis. Here are a couple of my own afterthoughts on it.

The existential crisis that all of the book’s main characters have to react to spans less than twelve hours. In such a situation, a ruthless reality focus on action over feelings is the price of survival, and it provides little time for nuanced internal self-reflection. The book actually provides several examples of characters who failed that test, as contrast.

As Grok correctly recognized, Randia’s “free-spiritedness” connects directly with the book’s theme about the value of personal independence. Thanks in part to the Archmage’s reforms, Carlissa is beginning to transition into the kind of society in which a princess could set aside some of her royal obligations to pursue a career as a bard. And despite the occasional need to send out the guards to escort her back to the palace, her family supported her in that choice. This was true not only of her brothers and parents, but especially her grandfather, the Archmage. (This is for reasons having to do with his own history. It will be revealed in time, but some of it is covered in the CRPG game module, The Quest.)